Tallulah Gorge is located in the northeastern corner of Georgia along the edges of the Appalachian mountains. At 1200 feet, it is the deepest canyon east of the Mississippi River, and within its boundaries are some of Georgia’s most stunning waterfalls. Deep within those boundaries also lies the story of Georgia’s first conservation movement.

In the mid-1800s, images of Tallulah Falls and Gorge began appearing in travel books, newspapers, and magazines giving rise to what would become a tourist boom by the turn of the century. At the height of the area’s popularity, 20+ resort hotels and boarding houses were operating in nearby towns. Savvy hotel owners proclaimed the Falls as the “Niagra of the South.”

However, it wasn’t just tourists who were drawn to Tallulah River and Gorge. In 1909, the Georgia Railway and Electric Company (now Georgia Power) struggled to generate enough electricity to sustain the growth of nearby Atlanta. The river, with its intense water flow and drops in elevation, seemed ideal for damming with the redirected water flow used to fuel new hydroelectric plants. Georgia Railway acted quickly by purchasing thousands of acres along the rim of Tallulah Gorge.

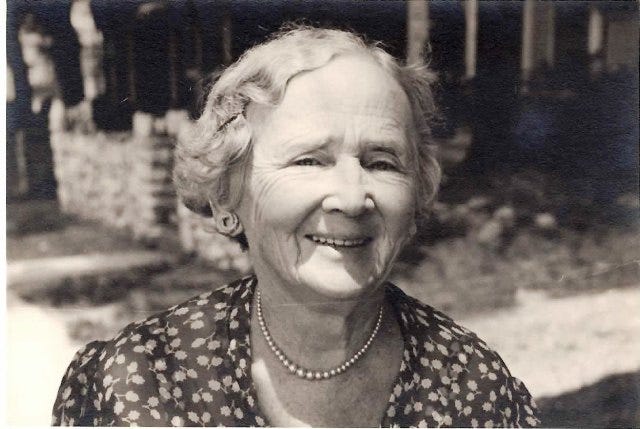

An hour away from Tallulah Falls, Helen Dortch Longstreet of Gainesville, Georgia monitored the power company’s land purchases. As an early conservationist and the widow of a hotel owner, she was increasingly concerned about a dam’s impact on Tallulah’s natural beauty and the area’s tourism-based economy. However, what everyone would soon learn was that Helen Longstreet wasn’t just a concerned citizen. She was, and always had been, a fighter.

At 2:00 a.m. Helen Longstreet awoke to a strange noise in her Gainesville, Georgia home. She rose from bed, retrieved her pistol, and crept down the hall. Approaching the dining room door, she saw a man attempting to open the silver closet. Helen called out and the intruder ran. She fired; he fired. Helen kept firing until her chamber was empty.

(Paraphrased from an undated newspaper clipping, The Longstreet Society)

Helen Dortch Longstreet’s record of fighting for people and places began when her father, James Dortch, an attorney and businessman, was convicted of corruption, drunkenness, and malfeasance while serving on the school board in Carnesville, Georgia. Helen was 15 and a gifted writer who had been working at the newspaper her father founded, The Weekly Tribune. She would use her writing skills to intensely campaign for her father’s innocence but unfortunately; James Dortch would die in a wagon accident two years later.

After her father’s death, Helen Dortch enrolled in Georgia Baptist Female Seminary, now Breneau University, in Gainesville, Georgia. It was there that she first met General James Longstreet. Longstreet had been a highly respected Confederate officer until his actions during the battle at Gettysburg led some to blame him for the Confederacy’s final defeat. The initial meeting between the two was brief but, as Helen subsequently rose to become one of Georgia’s most visible women, Longstreet sought a second meeting with her. An opportunity surfaced when Helen went to work for Governor William Yates Atkinson, an old friend of Longstreet’s. At the General’s request, the Governor arranged a meeting for the two and they would eventually be married on September 8, 1897. Helen was 34 and Longstreet was 76. Helen maintained that Longstreet was the love of her life and, indeed, her devotion to him was unwavering. When the General died six years after their marriage, Helen made restoring his military reputation her primary life’s work.

Although much of Helen’s time was consumed by defending General Longstreet, she continued to follow the Georgia Railway and Electric project in nearby Tallulah Falls. In 1910, she urged area business owners to join her in fighting the proposed dam and preserving the area’s scenery and wildlife. But few seemingly had the patience or resources for what they believed would be a protracted and expensive fight. With no local support, Helen used her funds and political ties to launch a statewide campaign opposing the dam. Her first step was to form the Tallulah Falls Conservation Association in 1911, which marked the beginning of Georgia’s first conservation movement.

Helen fought Georgia Railway on two fronts. First, she argued that definitive ownership of the land could not be established because the Tallulah Falls and Gorge area had never been formally surveyed. Further, she suggested that, even if it was determined that the company owned the land, that ownership did not give them the authority to use the resources of the falls or gorge. Helen successfully argued her position to a political ally, Governor Hoke Smith, who ordered a new survey of the area. That survey revealed that approximately 300 acres were not owned by Georgia Railway or any other entity and thus were under state control. Armed with this finding, Helen moved on to the state legislature. There, she secured a resolution urging Governor Smith to temporarily halt construction of the dam while the state’s land rights were being determined in court.

While the case made its way through the legal system, Helen also launched a public campaign using everything she had learned from defending her father and General Longstreet. She wrote articles and editorial pieces for regional newspapers and magazines frequently referring to Georgia Railway and Electric as …”commercial pirates and buccaneers…” who were trying to plunder “the most wonderful natural asset of the Western Hemisphere.” Helen also reached out to friends for support. In an undated letter to Georgia Senator Rebecca Fenton, she implored, “Can’t you help me about Tallulah? It is necessary to set up a fund to fight it out in the courts. Do come to my aid with a little advice if nothing else.”

Meanwhile, Georgia Railway countered Helen’s efforts with a public relations offensive. The company argued that the proposed dam would not significantly interfere with the water flow that fueled Tallulah’s five scenic waterfalls and thus would not damage tourism. However, when evidence to the contrary surfaced, the company pivoted and argued instead that the dam would enhance tourism by creating several new lakes for boating and fishing. After a two-year battle, Georgia Railway prevailed in the courts and the 126-foot high, 426-foot wide dam was constructed in 1913 with the first of what would eventually become six hydroelectric plants opening in 1914. The roaring Falls and the tourists they summoned all but disappeared.

Helen Longstreet’s fight with Georgia Railway left her financially strapped and exhausted. In 1922, she wrote to Senator Fenton again, “I struggled through a woe of poverty…following my sacrifices for Tallulah Falls.” During this period, Helen returned to the familiarity of Breneau where she taught classes and worked as a freelance author. Many of her writings continued to focus on the defense of her late husband, General Longstreet, but she also addressed Progressive-era issues including civil rights and women’s suffrage.

When World War II began, Helen Longstreet trained to become a Riveter as part of her larger effort to encourage women to work in the defense industry. Life magazine picked up her story in 1943 and Helen said of her training, “I was head of my class…In fact, I was the only one in it.” Following her training, Helen was hired by the Bell Aircraft Plant in Marietta, Georgia where she worked an 8:00-5:00 shift each day. She was 80 years old.

In 1957, Helen Longstreet’s lifetime of advocacy for people and issues important to her ended when she was found wandering the streets of upstate New York with no memory of who or where she was. She likely suffered a stroke, but with few rehabilitation facilities at that time, she was transported back to Georgia and the state mental hospital at Milledgeville. She died there on May 3, 1962 at the age of 99.

Eighty years (1992) after the completion of the Tallulah dam, Georgia Power leased 3,000 acres to the State of Georgia for the purpose of creating Tallulah Gorge State Park. The company also agreed to redirect water from their power operations back to the river on designated days to support tourism, especially white water rafting. Seven years later, Georgia Power acknowledged their once fierce adversary by naming the extensive trail system around the gorge for Helen Dortch Longstreet. In doing so, company spokesperson John Sell noted, “She was a woman way ahead of her time…It’s appropriate to honor her.”

Helen’s Other Accomplishments

Appointed as Georgia’s first female Assistant State Librarian making her the state’s first female employee

Appointed the first female postmaster in Gainesville, GA.

The first woman in Georgia to have her portrait placed in the state capitol

Inaugural supporter of Georgia State College of Women in Milledgeville

Inducted into Georgia’s Women of Achievement

Videos

Sources

http://www.longstreetsociety.org/helen-dortch-longstreet.html.

http://Gardner, Sarah. "Helen Dortch Longstreet." New Georgia Encyclopedia, 09 May 2003, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/helen-dortch-longstreet-1863-1962/.

http://McCallister, Andrew. "Tallulah Falls and Gorge." New Georgia Encyclopedia, 18 July 2003, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/geography-environment/tallulah-falls-and-gorge/.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/geography-environment/tallulah-falls-and-gorge/.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/exhibition/seven-natural-wonders/

https://www.tallulahfallsgeorgia.org/history-of-tallulah-falls/.

https://archive.org/details/tallulahfalls0000calh/mode/2up?view=theater

https://chattoogariver.org/the-tallulah-gorge/

https://rabunhistory.org/newsletters/september-2019-newsletter-helen-dortch-longstreet-fighting-lady/.

https://rabunhistory.org/articles/electricity-for-atlanta-six-hydroelectric-dams-a-submerged-town-and-silenced-waterfalls/.

https://www.thenortheastgeorgian.com/regional/woman-ahead-her-time.

https://www.franklincountycitizen.com/local-regional/woman-ahead-her-time.

https://books.google.com/books id=1lYEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA38&pg=PA37#v=onepage&q&f=false.